Cher visiteur,

Notre site internet est en cours de transformation en vue d’intégrer l’ensemble des éléments formant le nouveau projet de la fondation.

Nous sommes impatients de pouvoir vous faire découvrrir ceci dans les prochaines semaines.

La Fondation Marcel Mariën

Notre site internet est en cours de transformation en vue d’intégrer l’ensemble des éléments formant le nouveau projet de la fondation.

Nous sommes impatients de pouvoir vous faire découvrrir ceci dans les prochaines semaines.

La Fondation Marcel Mariën

Woman by woman : The representation of sexuality by 4 Belgian surrealist painters

mars 09, 2024

La connaissance des femmes appartient à la femme.

Paul Eluard in the preface of Dons des féminines, by Valentine Penrose

Paul Eluard in the preface of Dons des féminines, by Valentine Penrose

The representation of women in the surrealist movements has been a theme widely debated these past years. Nevertheless, because of its importance in quality and in quantity, many aspects of this subject remain insufficiently explored. It is the case of the representation of women by women in paintings as well as in literature.

In art history as in many academic fields, the weight of masculine vision has been so anchored in our society that most women still do not realize how they have been analysing history through the distortions they were taught by generations of male professors. The study of female representation in art has mostly followed this vision and many studies and comments are to be found on how accurate, romantic, beautiful, sexy, diabolic, ordinary, intelligent, stupid, feminine, or not, the female representation in painting and photography is. Among many others, studies as Surrealist Masculinities by Amy Lyford[1], or the “male gaze” famously theorised by Laura Mulvey[2] as early as in 1975 show with no ambiguity how male artists objectivise the female body and how, often with the excuse of a Freudian interpretation, women are reduced to a hollow shell for men’s own desire. In surrealist images, this translates into female bodies of young women corresponding to the cannon of beauty in vogue (Man Ray, Dali, Delvaux), that of monstruous creatures that corrupt the world (Dali, Ernst, Bellmer), or the mixture of both.

But very few have enquired about the representation of the female body by women artists. The recent exhibition at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Women painting Women[3] has provoked interest in the subject, but the period illustrated goes from the sixties to today, with a focus on the contemporary artists; also and typically for todays prude USA, the exhibition avoids, as much as possible, the themes of nudity and sexuality. Interestingly, the very recent publication Painting her pleasure by Lauren Jimerson[4] studies in depth this very theme for three women artists - Valadon, Charmy and Vassilieff- in France at the turn of the 20th century. This article would like to stimulate such reflexions applied to the surrealist movements, where precisely love, sex and women are a major preoccupation. I will evoke here the gaze of four women artists, all considered Belgian Surrealists or their heritage. Again,

[1] Surrealist Masculinities, Gender Anxiety and the Aesthetics of Post-World War, University of California, 2007

[2] Laura Mulvey , Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, 1975

[3] Women Painting Women, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, curated by Andrea Karnes

[4] Manchester University press, 2023

this is not a research, merely a glance in a very intricate and changing subject that still needs to be addressed in all its complexity.

Being the eldest, Suzanne Van Damme, born in 1901, is the one I will begin with.

Van Damme has a very large and varied production in the representation of women during over 50 years. Between the mythical drawings of the early 1940ies her anthropomorphic female figures of the latter part of her career one observes a natural diversity of styles, but also some common aspects.

Suzanne Van Damme, untitled

Two characters, represented in a faded, indefinite manner and space, face each other bodily being almost the same size. On the left side, a naked woman seems to be walking, her breast prominent and looking vaguely at the second figure. She is in action and seems to be in command of herself. The second figure is at halt, looking on the side, not at the woman, and its gender and nakedness are less defined. The viewer is equally attracted to the faces and to the bodies. Their nakedness enhances the strength of the expressions and of the movements, but it does not stimulate a sexualized gaze, as the womanhood of the left figure is obvious, but also real, not idealized. The general impression could be compared to a mythological scene, where naked characters appear undressed, courting or not, without a sense of sexual domination.

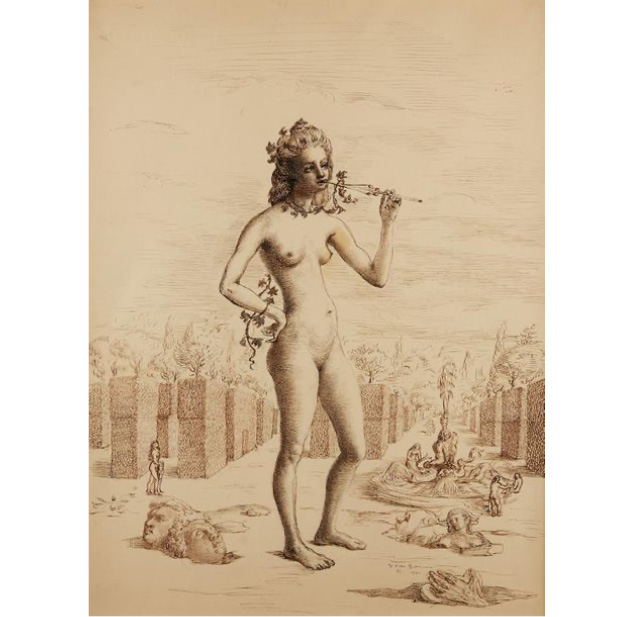

Very differently, a precious ink drawing dated 1941 shows a young standing naked women in an Italian style garden, surrounded by gruesome chopped heads and hands and other small female nudes, most probably the illustration of a story I am ignorant of.

Suzanne Van Damme, title unknown, 1941, brown ink on paper

This female nude is young, beautiful [5], and Van Damme draws all the feminine attributes in a perfectly obvious manner. Despite this, despite her elaborate hairdo, her intricate beauty, again the figure does not appear as a body attractive (hetero)sexually. The expression on her face suggests that she knows and does what she wants, opposed to being open to the fantasies of a hidden companion. But more importantly, her position is peculiar: the positioning of her legs and of her arms, the swaying of her hips is not that of the usual position of a women, but more that of a man, thus disrupting the normative body language of sexual messages.

[5] the strong Renaissance inspiration points out to Pisanello’s drawings

In Le Masque du refus of 1952, the main female body is decomposed and reassembled, a method Van Damme often used. Here everything suggests the control that the woman has on her actions: the title, the choice of the masque, the impression of multiplication of her breasts

her long neck, her dominant position, the blackness of her hair. On the contrary the blond “king figure” suggests retreat, almost a bashful defeat, turning his head away.

Suzanne Van Damme, Le Masque du refus, 1952

Sexuality is certainly an important part of the picture’s theme, but here it is clear that it is the woman that leads the dance.

Many other works by Suzanne Van Damme indicate women’s reappropriation of their body and their sexuality by suggesting to accept another approach to femininity, an approach that involves not only their body, but also their intellect. In her paintings, woman play and are active, while ignoring or inverting the usual order of roles between sexes.

This could also be said about Jane Graverol's representation of the female body. But her interests are some what different and the worlds she creates are of another kind.

When she addresses the subject of Apollinaire's poem Le cortège d'Orphée[6], it is not to illustrate it, but rather to use it for the expression of her own feelings. "J'étais terriblement sincère; mes peintures étaient l'expression de mes sentiments passionnels et de mes sensations"[7]

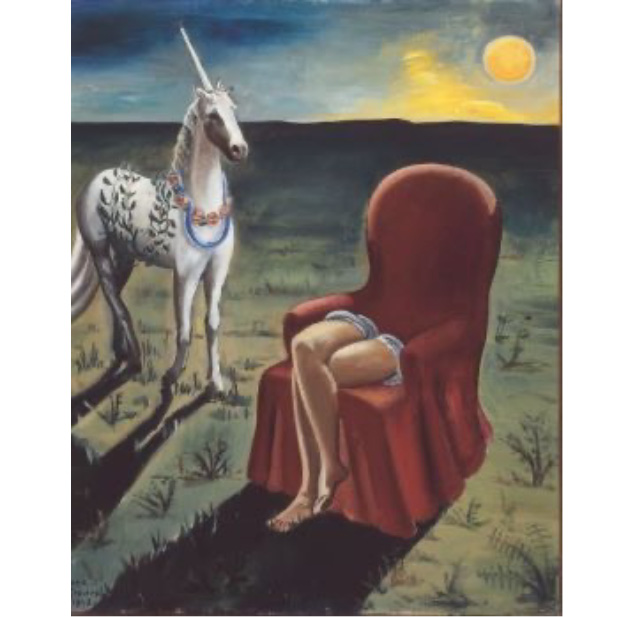

Significantly, in the original illustrations by Raoul Dufy the horse has wings; in JG's version it has become a unicorn, a symbol with so many meanings. Here the women's body is present only by her crossed legs, softly introduced with white linen and contrasting with the red drape

[6] the strong Renaissance inspiration points out to Pisanello’s drawings

[7] The poem illustrated here is that of the Horse : Mes durs rêves formels sauront te chevaucher, Mon destin au char d’or sera ton beau cocher, Qui pour rênes tiendra tendus à frénésie, Mes vers, les parangons de toute poésie.

of the almost anthropomorphic coach it "sits" on. The absence of the rest of the body deprives the viewer of the sexual pleasure suggested by the legs, a sexual pleasure that exists, is specifically feminine, but that is not shared.

Jane graverol, Le cortège d’Orphée, 1948, oil on canvas, 70 x 50 cm, Collection of the Fédération Wallonie- Bruxelles

Beside the pointed horn, references to masculinity are absent from the painting.

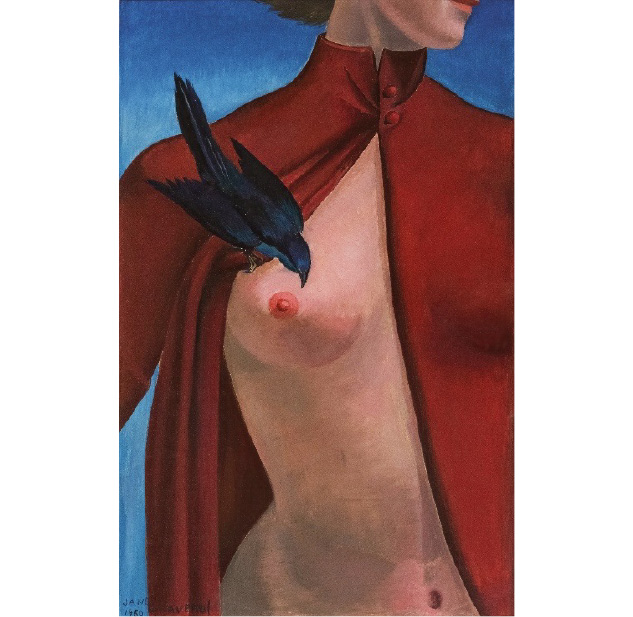

We can see the same absence in Le Sacre du Printemps from 1960. Here Graverol again choses to show only a part of the body, with the vision of a firm breast.

Jane Graverol, Le Sacre de Printemps, oil on paper, 46 x 30 cm 1960

The bird, often symbol of physical action and pleasure, is about to prick the nipple, thus spoiling any desire the viewer could have had otherwise and introduces forcefully the notion of female pain, despite the perfect beauty of the figure. Partial vision of a sexualized body, lust spoiled by something squeaky and painful, nature taking over or helping her are some of Graverol’s tools to either defend herself from violence or to affirm the full command she has on herself.

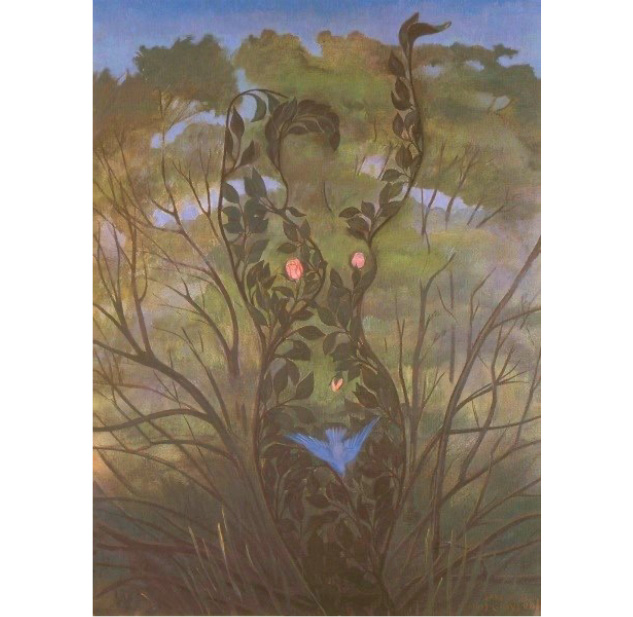

Jane graverol, La frôleuse, 1969

An artist open to new situations, Jane Graverol will evolve and integrate the free spirit of the sixties, as we can see in her later representations of women, where, with some exceptions (devils and flames), less tensions are expressed and the female naked body stands strong and independent, more often in harmony with its environment and is used as the vehicle of messages she choses to divulge.

Rachel Baes, born in 1912, is a more spontaneous and intuitive artist. Her figures are a response to the surrealist pattern of the "femme-enfant" so popular in the circle of André Breton and many others. But instead of depicting the consenting and idealised very young muse, she shows without detours the violence imposed on them. Sex is central to Rachel Baes’ works. Sex as a obvious consequence of female being, or as an imposed profession, as revealed by Patricia Allmer in this year’s catalogue Le surréalisme en Belgique[8].

« le thème du travail féminin est au cœur des œuvres de ces trois femmes artistes. (…) chaque œuvre explore le rapport (…) entre les représentations des femmes et la pratique esthétique surréaliste »

[8] Patricia Allmer, Une pièce de dentelle : production genrée et travail esthétique chez Rachel Baes, Jane Graverol et Irène Hamoir, Le surréalisme en Belgique, Bruxelles, 2024

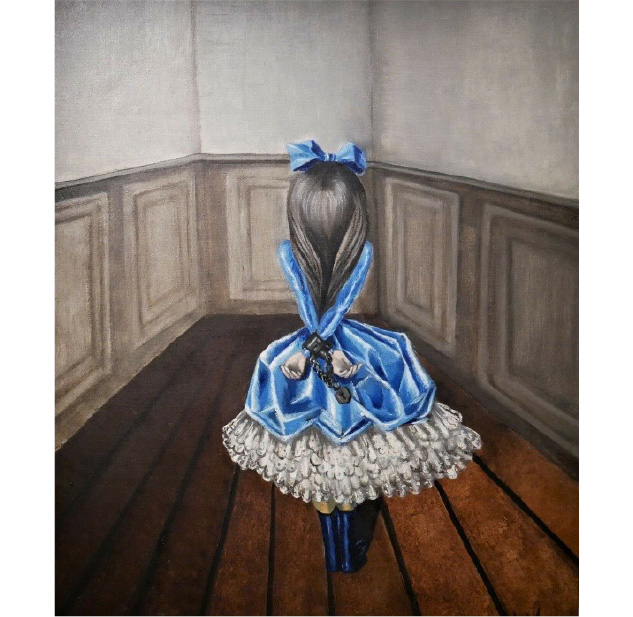

Rachel Baes. "La première leçon" 1951

In this small but clear image, Rachel Baes imposes to the viewer the absurdity of the sexualized child. She choses to conceal the young girl’s face as a response to the seductive femme-enfant faces of male surrealist artists. Her femineity is represented by the boots and the exaggerated dress; her childhood by the bow in her hair and her small size. The subject here is not the pleasure of sex, but the pain it inflicts on the child.

Rachel Baes, The bottomless pit, 1955

In The bottomless pit, 1955, again the painter enhances the young working women’s bodies through moulding, monochromic and theatrical dresses, attracting one’s attention on their prominent, provoking breasts, the high boots and their youth. Yet she also desexualizes them by their macabre grey faces and grey hair, by the emptiness of their eyes and by the coldness of the moonlight, linking their bodies as well as their minds to the notion of suffering.

Rachel Baes’ images show the female condition with no detour and seem to address a female public. The success of her paintings with her male fellow-artists reveals the confusing contrast between their revolutionary spirit and their feelings about love, sex and women in general.

Going on to a more recent generation, painter Danielle is a post-war artist, born in 1944. Her reaction to the “male gaze” is defiant and provocative. The images she creates in the sixties and the seventies show a variety of naked women ornamented with plants that point obviously to sexual associations; she also paints plants alone as anthropomorphic sexual body parts.

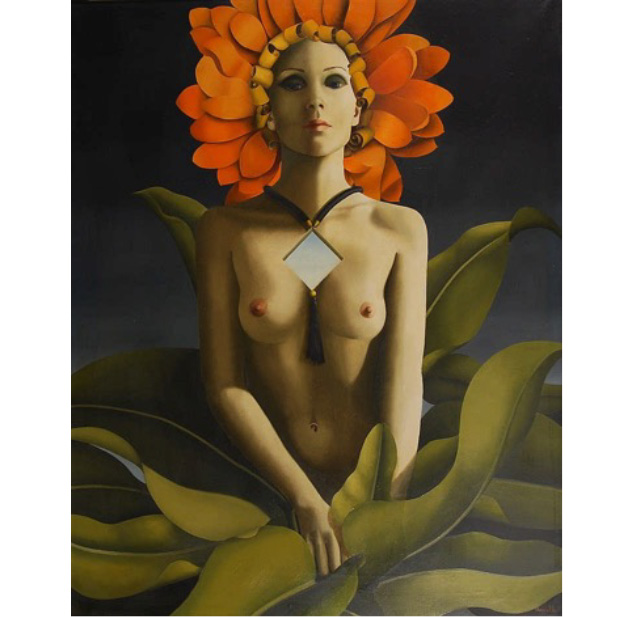

Danielle, Nu au nénuphar , oil on canvas. 100 x 80 cm.

Women as blossoming flowers, meant to attract pollinizing insects in an extraordinary variety of ways. In Nu au Nénuphar, a young beautiful women proudly exhibits her nude chest with a defiant expression, and states that she only is in command of herself. The “insects” that would try to approach are warned. Danielle modulates light and shadow to sculpt the body in an insolent manner, and reveals a women coming out of the darkness; the mirror-necklace around her neck is an extra game of attraction and distancing.

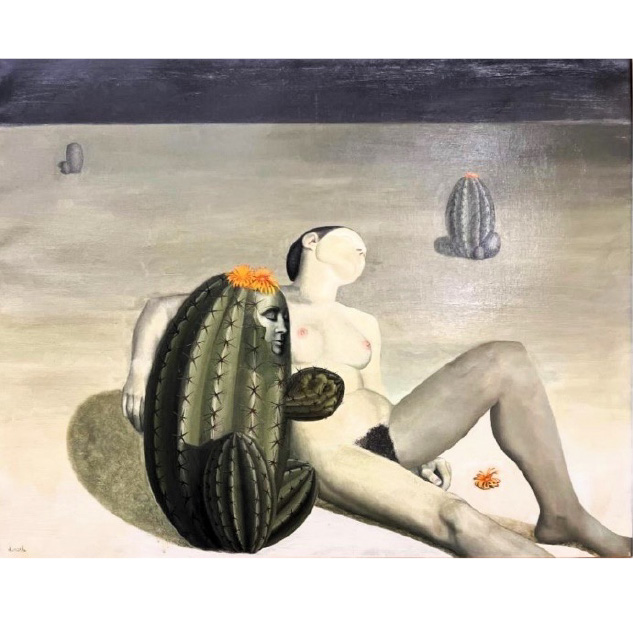

Danielle, untitled, oil on canvas, 80 x 100 cm

In this work picturing a nude in a desert with cactuses, the allusion to masculinity is quite obviously contained in the cactus in the front, with a creaky and painful association. Although the naked young woman seems to be caught in the moment after action and seems peacefully indifferent to her surroundings, the viewer cannot ignore the contrast between the anthropomorphic cactus that the woman’s arm embraces gently and the needles of the cactus. Again the idea of stinging such beauty emerges, as if to spoil the pleasure of the male gaze, whilst showing the indifference of the female figure.

How Danielle expresses her vision of lust and sex can be considered an influence of the liberation movement of her time, but her images also reveal the daring spirit of an artist that freely follows her own path.

To succeed and to persevere as a professional artist, for a woman born over one hundred years ago, so many obstacles needed to be defeated that only the stronger ones would survive. Their strength was not to be seen only in their professional, but also their intimate life. They expressed this in their art as openly and freely as they would chose to, with results that fundamentally differed from the images created by their male fellows.

I can only encourage the readers to deepen their knowledge on these great artists by the lecture of the existing studies about them.

Hélène de Zagon